Is that black mold on your t-shirt?

Moldy t-shirts and clothing are normally . . .

cleaned when contaminated with mold. Putting a slightly different twist on this new story that incorporates mold and bacteria as a substitute dye used for clothing. This leads us to the question, “if mold is being used as a dye, how can these researchers remove all bad things that go along with mold?” Most people become allergic to the little pieces of mold, mold spores, and sometimes react to the mVOCs (microbial volatile organic compounds). Let’s see if the research below can break the mold about how people ultimately view these harmful organisms.

Zemanta Related Posts

Two master’s students from the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) are trying to spark the country’s interest in the sustainable fashion movement by developing items colored with fungus and bacteria, including those that can be easily found in your bathroom.

Don’t you hate it when black mold grows on your white shirt? Instead of trying hard to clean it with bleach or vinegar, you could let the mold grow further, giving a splash of new color to your old shirt.

The idea perhaps sounds silly, but that is exactly what Nidiya Kusmaya had in mind when she started her final thesis at ITB.

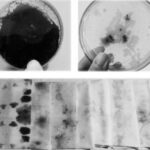

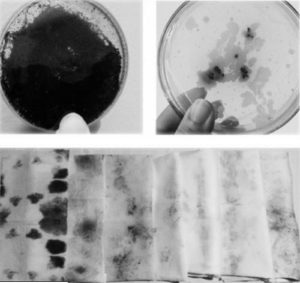

She discovered the hidden beauty of Aspergillus niger, a micro fungus responsible for the black mold on damp clothes.

“People see Aspergillus niger as something disgusting, something to avoid. In fact, the fungus is valuable; it can act as a pigment producer in textiles,” said Nidiya, an awardee of the leading scholarship from the Foreign Cooperation Bureau (BU BPKLN) of the Research and Technology and Higher Education Ministry.

Research conducted previously in the United Kingdom on pigment-producing bacteria prompted her to discover the interesting shades produced by fungus and bacteria that thrive in the tropical climate of Indonesia.

Aside from the black Aspergillus niger, she also cultivated two other fungi: the orange Monascus sp. and the white Trichoderma.

“Monascus can harm plants, but not humans. It can be found in the traditional Chinese medicine angkak [red yeast rice]. Meanwhile, Trichoderma fertilizes soil,” she said.

Nidiya also experimented with Serratia marcescens, a red and pink bacterium that usually grows in the corners of bathrooms.

“It can cause infections, but using it as a pigment producer is safe,” she said, adding that garments coated with the bacteria were sterilized at an elevated pressure and temperature in an autoclave.

Nidiya only uses natural fabrics like silk and cotton because they can withstand the heating process.

Little wonder: Nindiya Kusmaya, a student of the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), works with a number of micro fungi and bacteria to create natural pigments in garments.

Little wonder: Nindiya Kusmaya, a student of the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), works with a number of micro fungi and bacteria to create natural pigments in garments.

In one neckwear collection, she sprinkled different fungus and bacteria onto the fabric and let them form natural patterns.

“It appears that bacteria and fungus can communicate. When they meet, they create bold colors,” she said about her research, which was conducted under the guidance of ITB lecturers Kahfiati Kahdar and Imam Santosa.

In another collection, she orchestrated the bacteria and fungus to form batik and tie-dye patterns.

Mold Growing on Shoes

“I drew patterns using antifungal and antibiotic pastes before applying the fungus and the bacteria. As a result, they did not grow on the specified areas on the garment,” she added.

Based on her experience as a professional textile designer, Nidiya believes that fungus and bacteria could provide a new avenue for the fashion industry — the world’s second most polluting industry, second only to oil, according to the Danish Fashion Institute in 2013.

“Coloring textiles requires loads of chemicals and it gives me a headache every time I need to dump the wastewater,” she said.

In contrast to chemical coloring substances, the wastewater of the fungus and bacteria-colored garments do not pose harm to the environment.

“I want to discover more bacteria and fungus, and combine them with natural coloring, such as turmeric. I hope it will inspire people to make an industry out of it,” Nidiya said, adding that the coloring process was not much different to making tempeh in a home industry.

Nidiya hopes to start a textile brand focusing on sustainable, biodegradable products to cater to her fashion designer clients who still favor natural pigments and the organic patterns that they produce.

She humorously describes one of her textile creations as looking like “a bloody crime scene on the Dexter TV series”.

“Perhaps the planned patterns are suitable for the general market, while the natural patterns belong to haute couture, serving as a fashion statement,” she said.

Sapta Soemowidjoko, another BU BPKLN awardee who recently completed his master’s degree in design at ITB, created a garment from Kombucha, a symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast popularly called scoby.

Moldy t-shirts and clothing are normally cleaned when contaminated with mold. Putting a slightly different twist on this new story that incorporates mold and bacteria as a substitute dye used for clothing. This leads us to the question, “if mold is being used as a dye, how can these researchers remove all bad things that go along with mold?” Most people become allergic to the little pieces of mold, mold spores, and sometimes react to the mVOCs (microbial volatile organic compounds). Let’s see if the research below can break the mold about how people ultimately view these harmful organisms.

Two master’s students from the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) are trying to spark the country’s interest in the sustainable fashion movement by developing items colored with fungus and bacteria, including those that can be easily found in your bathroom.

Don’t you hate it when black mold grows on your white shirt? Instead of trying hard to clean it with bleach or vinegar, you could let the mold grow further, giving a splash of new color to your old shirt.

The idea perhaps sounds silly, but that is exactly what Nidiya Kusmaya had in mind when she started her final thesis at ITB.

She discovered the hidden beauty of Aspergillus niger, a micro fungus responsible for the black mold on damp clothes.

“People see Aspergillus niger as something disgusting, something to avoid. In fact, the fungus is valuable; it can act as a pigment producer in textiles,” said Nidiya, an awardee of the leading scholarship from the Foreign Cooperation Bureau (BU BPKLN) of the Research and Technology and Higher Education Ministry.

Research conducted previously in the United Kingdom on pigment-producing bacteria prompted her to discover the interesting shades produced by fungus and bacteria that thrive in the tropical climate of Indonesia.

Aside from the black Aspergillus niger, she also cultivated two other fungi: the orange Monascus sp. and the white Trichoderma.

“Monascus can harm plants, but not humans. It can be found in the traditional Chinese medicine angkak [red yeast rice]. Meanwhile, Trichoderma fertilizes soil,” she said.

Nidiya also experimented with Serratia marcescens, a red and pink bacterium that usually grows in the corners of bathrooms.

“It can cause infections, but using it as a pigment producer is safe,” she said, adding that garments coated with the bacteria were sterilized at an elevated pressure and temperature in an autoclave.

Nidiya only uses natural fabrics like silk and cotton because they can withstand the heating process.

Little wonder: Nindiya Kusmaya, a student of the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), works with a number of micro fungi and bacteria to create natural pigments in garments.

Little wonder: Nindiya Kusmaya, a student of the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), works with a number of micro fungi and bacteria to create natural pigments in garments.

In one neckwear collection, she sprinkled different fungus and bacteria onto the fabric and let them form natural patterns.

“It appears that bacteria and fungus can communicate. When they meet, they create bold colors,” she said about her research, which was conducted under the guidance of ITB lecturers Kahfiati Kahdar and Imam Santosa.

In another collection, she orchestrated the bacteria and fungus to form batik and tie-dye patterns.

“I drew patterns using antifungal and antibiotic pastes before applying the fungus and the bacteria. As a result, they did not grow on the specified areas on the garment,” she added.

Based on her experience as a professional textile designer, Nidiya believes that fungus and bacteria could provide a new avenue for the fashion industry — the world’s second most polluting industry, second only to oil, according to the Danish Fashion Institute in 2013.

“Coloring textiles requires loads of chemicals and it gives me a headache every time I need to dump the wastewater,” she said.

In contrast to chemical coloring substances, the wastewater of the fungus and bacteria-colored garments do not pose harm to the environment.

“I want to discover more bacteria and fungus, and combine them with natural coloring, such as turmeric. I hope it will inspire people to make an industry out of it,” Nidiya said, adding that the coloring process was not much different to making tempeh in a home industry.

Nidiya hopes to start a textile brand focusing on sustainable, biodegradable products to cater to her fashion designer clients who still favor natural pigments and the organic patterns that they produce.

She humorously describes one of her textile creations as looking like “a bloody crime scene on the Dexter TV series”.

“Perhaps the planned patterns are suitable for the general market, while the natural patterns belong to haute couture, serving as a fashion statement,” she said.

Sapta Soemowidjoko, another BU BPKLN awardee who recently completed his master’s degree in design at ITB, created a garment from Kombucha, a symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast popularly called scoby.

Kombucha can be easily found in Chinese traditional medicine stores and can be used to make Kombucha fermented tea. While the health benefits of Kombucha are still debated, it could certainly be used for fashion items.

Inspired by Kombucha material created by New York-based designer Suzanne Lee, Sapta added a twist to the ground-breaking garment by combining it with a web of bamboo threads.

The current fashion industry heavily depends on animal and plant-based fibers, such as silk and cotton. Kombucha material could be a solution, but Sapta understands that many people still have doubts about wearing bacteria and yeast as clothing.

Thus, he combines the material with something familiar — bamboo threads.

“Kombucha material has been used as a medical textile and amplifier, so why can’t it cross into the fashion world?” he said. “I created this fabric to serve as a bridge for us to reach a fashion future.”

In his research conducted under the guidance of ITB lecturers Kahfiati Kahdar and Andar Bagus Sriwarno, Sapta pulped the scoby in a food processor and put it in a rectangular container. He placed a web of bamboo threads in the box as the Kombucha juice grew.

After trial and error, he managed to get the desired result, in which the bamboo web was inside a Kombucha blob. After it reached 2 centimeters in thickness, the newly made garment was washed and dried.

While the trial and error seemed arduous, the fact that Sapta cultivated the garment in his house gives hope that other people could develop the process into a home industry.

“To attach the garment pieces to one another, you just need to iron them. You can hand-stitch and cut them with scissors and multi-cutting devices,” he said.

For his final thesis, Sapta developed Plan B, a bowtie and suspender collection to represent the synergy of science and art in the products.

“I chose bowties because they are synonymous with scientists. Plan B basically means our next plan. B stands for bacterial cellulose, bamboo, a bridge to a fashion future,” he said.

Sapta hopes his research can inspire another slow fashion initiatives and, in the long term, help to slowly reduce the dependency on plant-based fibers.

Slow fashion, which is still largely unheard of in Indonesia, is a growing trend within the fashion world for sustainable, ethical clothing. It is the opposition of the “fast food” approach to fashion, namely fast and cheap production that results in exhausted resources and excesses of barely used clothing.

Slow fashion still has some challenges to overcome, though. The acidic smell of the Kombucha garments, for example, could be the main hurdle for it to be accepted by fashionistas.

“People always want to smell nice. It is understandable that when you wear the garment, you don’t want people to sniff you and assume that the pungent smell comes from your body,” Sapta said.

But, he said, wearing a little bow tie will not lead people to smell you. Instead, it gives you an interesting conversation topic at parties, where people will approach and ask: “Where did you get that bowtie?”

– See more at: http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/03/07/growing-fungus-and-bacteria-textiles-fashion.html#sthash.GLgs2SWq.dpuf

Leave a Reply